Read the content in English

We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land we now call Australia.

We recognise that their sovereignty has never been ceded.

When we use the term Aboriginal we refer to the diverse cultures of the mainland and the Torres Strait region (over two hundred islands located in the Australian continent, between Cape York and Papua New Guinea) of the country we now call Australia. Aboriginal cultures are still strong, vibrant, and are considered the world’s oldest continuing cultures. They all have different cultures, languages, histories and experiences, but most share the importance of their cultural heritage and strong bond with the land. For this reason, recognising that the rights of Aboriginal peoples to their lands have never been ceded even after colonisation, is an act of respect in contemporary Australian society, which recognises the deep bond that the first inhabitants have with the territories of which they have been taking care of for millennia. The roots of the ‘Acknowledgment of Country’ (literally, ‘Recognition of the Lands’) go back to traditional protocols used by Aboriginal peoples to welcome members of other communities in their territory. In order to access it, visitors had to recognise the hosts’ sovereignty over their lands and respect their rules. This importance still remains today, and the Acknowledgment is used to initiate public meetings across Australia (by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people). Why is it important to recognise Aboriginal sovereignty outside Australia. Wherever we are, it is important to recognise the sovereignty of Aboriginal people, who never – at any point – ceded authority over their land and rights to their culture throughout the violent process of invasion, dispossession and colonisation.

WARNING

We inform visitors that these images show Aboriginal people who have died, and that some of this content relates to topics and events relating to the colonisation of Australia that may be sensitive. It is important to indicate this as a sign of respect, as in Aboriginal cultures the protocols for mourning can vary according to groups, families, and individuals. However, it is common practice to suppress public photos of the deceased for a timeframe decided by the communities themselves. In contexts such as those of a museum, where there are multiple historical photographs of deceased people and descriptions of stories relating to colonisation, it is a sign of respect to point this out to visitors, to allow them to choose whether to look or not at the material.

‘Aboriginal Archives in Italy’: a collaborative and participatory research project

I’m Monica Galassi, an Italian researcher currently living in Australia. I am part of the Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research, at the Sydney University of Technology, where I am also doing my PhD. My studies focus on the importance of Italian archival material for Aboriginal communities and for the reconstruction of colonial history. It was in fact during the “voyages of discovery” that gave rise to colonial empires, that European explorers, missionaries, and scientists travelled to the country we now call Australia, and wrote notes and took photographs of Aboriginal peoples, customs, and languages, from their point of view and perspectives. A significant amount of this information was sent back to European museums, archives, and churches: the testimonies of Captain D’Albertis are an example. Still, many projects worldwide are increasingly discovering more about the Aboriginal peoples in these photographs and give voice and control to communities through promoting new community-led narratives, forms of art, photography, and digital media. In this context, the Aboriginal Archives in Italy project was born as part of my doctoral studies. The main objective is to facilitate access and mutual and collaborative research on archival documents relating to Aboriginal Australian peoples held in Italian institutions. It also aims to establish connections between Italian institutions and the Aboriginal communities represented in these archives, promoting opportunities for future collaborations between Italy and Australia. The project uses a digital platform created specifically for access to Indigenous cultural heritage, called Mukurtu (pronounced MOOK-oo-too, which in the Aboriginal language Warumungu means dilly bag, “a safe place to store sacred materials”). I have adopted it to facilitate access to information in Italian institutions for both Aboriginal communities and Western cultural institutions in culturally respectful ways.

Monica Galassi – Researcher at the Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research and PhD Candidate, University of Technology Sydney (UTS).

You can watch the interview with Monica Galassi, with additional information on the development of the concept for this section of the exhibition by clicking on the link https://aboriginalprojectitaly.com/en_au/watch-the-videos/

How would you feel if…

…You discovered there were photographs of your mother, father, grandmother or grandfather held in an institutional archive far from home? What if the photographs had been acquired by the institution a long time ago – possibly over the last century – and had been publicly displayed in exhibitions and online? What if the name of your ancestors and the contextual information about the photographs was missing, incorrect or racist? These questions confront Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people whose images, knowledges and languages among many other significant aspects of our cultural heritage were captured and documented by missionaries, explorers, anthropologists, government officials, painters and photographers and dispersed throughout institutional archives globally, often without the informed consent of our ancestors. Institutional archives were never designed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s contemporary responses and access to the collections in mind. Instead, we were historically represented as a curiosity and regarded as a dying race. But we are still here – our culture vibrant, our voices strong. Without our stories enriching the collections, these materials are unimbued with real meaning. It is more important than ever for institutions to amplify our sovereign voices as part of their ongoing commitment to decolonisation. The D’Albertis Museum is one such institution beginning to take important steps to connect with the descendants and communities of the people who are depicted within their collections, in this case, within the photographs of Captain D’Albertis and J.W. Lindt.

Marika Duczynski (Gamilaraay). Writer, Curator and Member of the Indigenous Engagement team at the State Library of NSW

You can watch the interview with Marika Duczynski, with additional information on her experiences working with archival records of Aboriginal and communities by clicking on the link https://aboriginalprojectitaly.com/en_au/watch-the-videos/

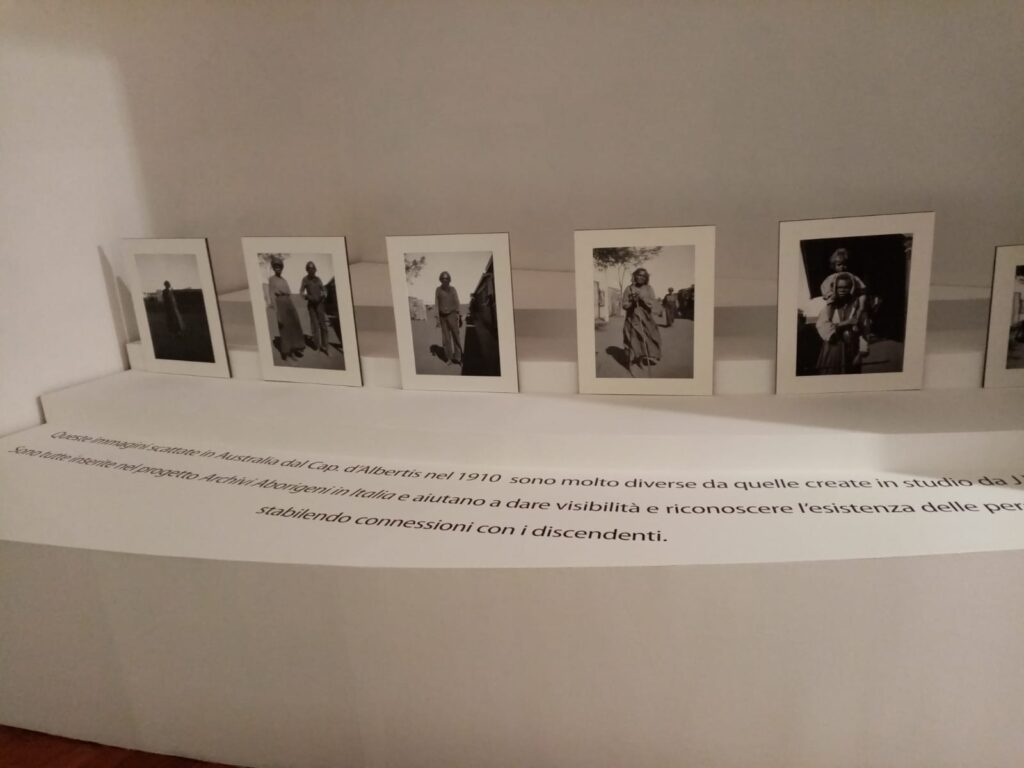

These images taken in Australia by Cap. D’Albertis in 1910 are very different from those created on a photographic set by J.W. Lindt in 1873. They are all included in the Aboriginal Archives in Italy project to give them visibility and to recognise the presence of the peoples represented, establishing connections with their descendants.

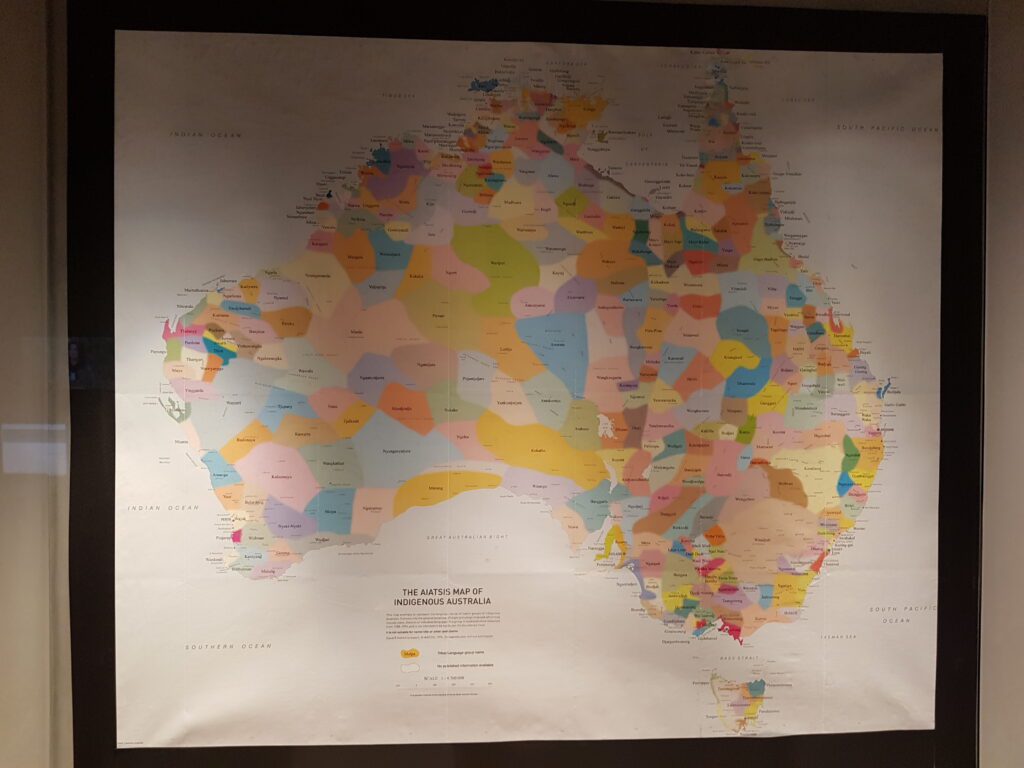

Map of Indigenous Australia

This map highlights the richness and diversity of Aboriginal languages and cultures across the Australian continent.

David R Horton (creator), © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), 1996.

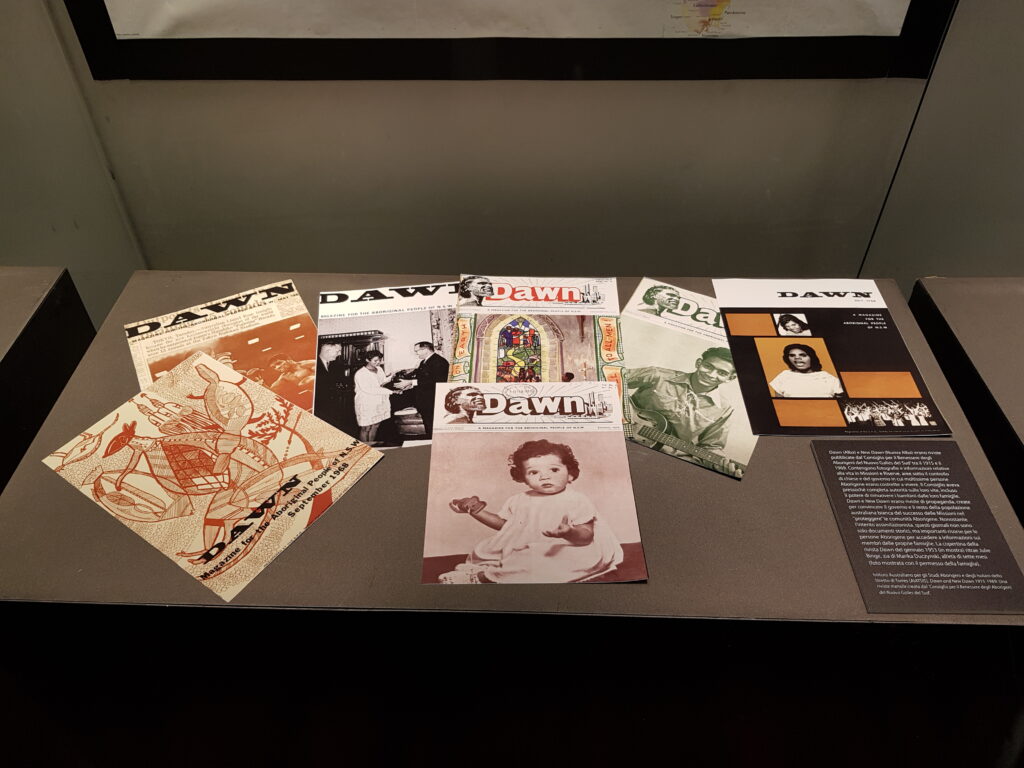

The Dawn and the New Dawn

The Dawn and the New Dawn were magazines issued by the NSW ‘Aborigines Welfare Board’, between 1915 to 1969. They contain photographs and information related to the life in Missions and Reserves, areas under church and government control where large numbers of Aboriginal peoples were forced to live. The Board had almost complete authority over their lives, including the power to remove children from their families. Dawn and New Dawn were magazines of propaganda, to convince government and the wider white Australian population of their success in the ‘protection’ of Aboriginal communities. Despite this assimilationist intent, the Dawn and the New Dawn are not just historical records, but significant assets for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today to find out information about family members. The cover of the Dawn Magazine from January 1953 (exhibited) shows Marika Duczynski’s Auntie Julie Binge as a seven-month-old baby (Photo showed with permission of the family).

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). Dawn and New Dawn 1915-1969: A monthly magazine produced by the NSW Aborigines Welfare Board.

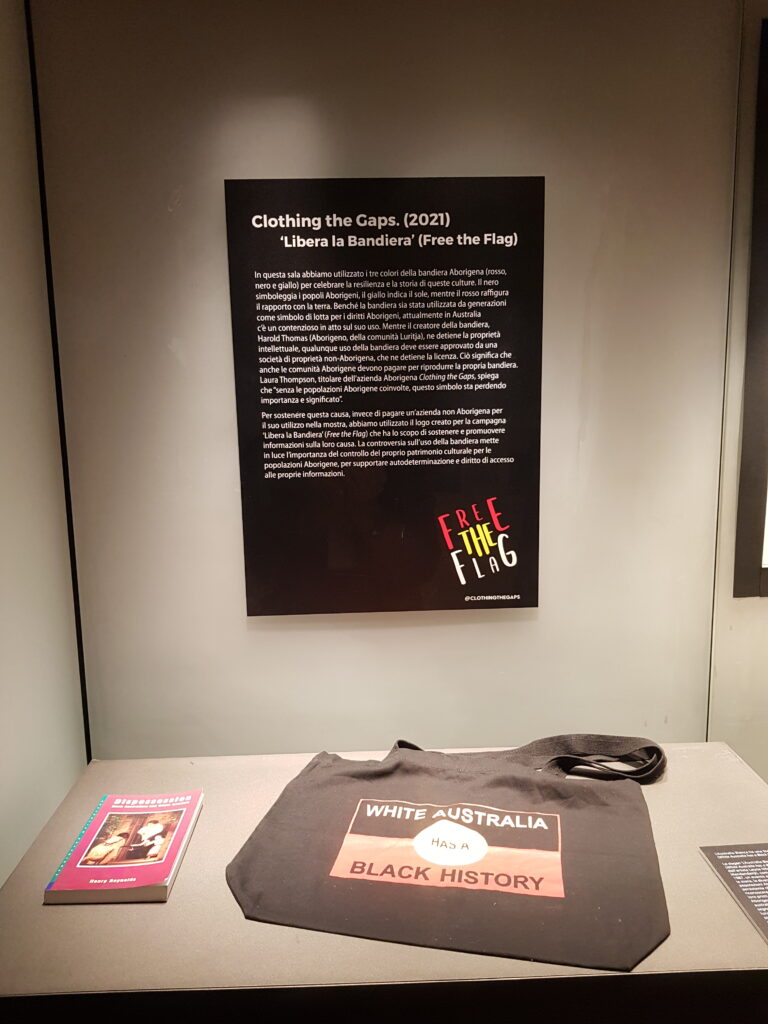

Clothing the Gaps. (2021)

‘Free the Flag’

As an icon for this room, we have used the three colours of the Aboriginal flag (red, black and yellow) to celebrate the resilience and the long history of these cultures. The black symbolises Aboriginal peoples, the yellow the sun and the red depicts the relationship with the land. Although the flag has been used for generations as a symbol of the struggle for Aboriginal rights, there is currently litigation in Australia over its use. While the flag’s creator, Luritja man Harold Thomas, owns the copyright, reproductions of the flag are licensed to a non-Aboriginal owned company. This means that even Aboriginal groups must pay to reproduce the flag. Laura Thompson, owner of the Aboriginal company Clothing the Gaps, explains that “without Aboriginal peoples involved this symbol is losing importance and meaning”. To support this cause, instead of paying a non-Aboriginal business for its use, we used the logo created for the Free the Flag campaign to support and share information on their cause. The controversy around the use of the flag highlights the importance of control of cultural heritage and information to support Aboriginal self-determination.

Clothing the Gaps. (2021). Free the Flag logo. https://www.clothingthegaps.com.au/pages/free-the-fla

The slogan White Australia has a Black History was created by Mandandanji artist Laurie Nilsen, as part of the 1987 NAIDOC competition, an event that is still held annually across Australia each July to celebrate the history, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal peoples. The slogan alludes to Australia’s enduring unwillingness to acknowledge past atrocities committed towards Aboriginal peoples, and the lack of inclusion of their perspectives in the telling of national history. Since then, the slogan has been used as a sign of protest by Aboriginal peoples and groups in their long-standing advocacy towards social justice in Australian society. These different movements also exposed the vital importance of control and transparency over Indigenous historical archives, and the inclusion of Aboriginal perspectives in reading the history of colonisation to achieve self-determination and concrete social equity.

Bag White Australia has a Black History. Personal collection.

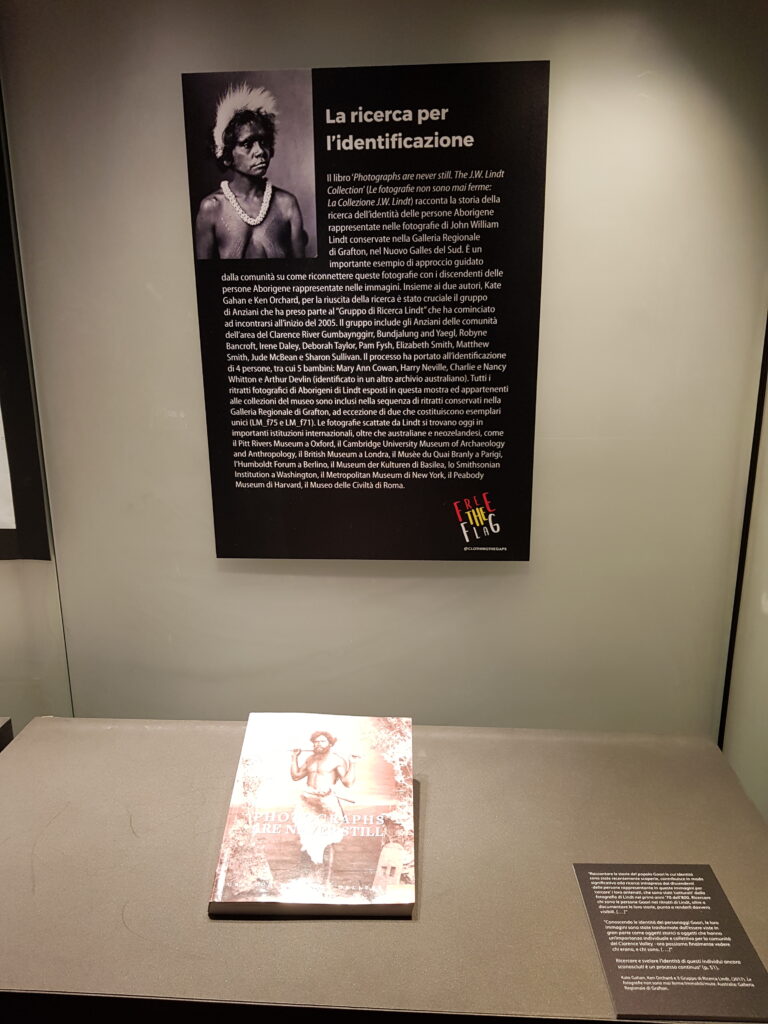

Kate Gahan, Ken Orchard & The Lindt Research Group. (2017). Photographs are Never Still: The J.W. Lindt Collection. Australia: Grafton Regional Gallery.

“Telling the stories of the Goori people whose identities have been uncovered to date contributes significantly to the quest undertaken by current day descendants to ‘look for’ their ancestors, who were captured photographically by Lint in the early 1870s. Researching who the Goori people in Lindt’s portraits are, as well as documenting their stories, aims to make them truly visible. […]”

“In knowing the identities of the Goori sitters their images have been transformed from being viewed largely as historic objects to items that have individual and collective importance to the Goori people, and communities, of the Clarence Valley – we now see who they were, and are. […]”

“Researching and revealing the identity of the individuals still unknown is an ongoing journey” (p. 51).

The search for identification

The book Photographs Are Never Still: The J.W. Lindt Collection tells the story of the search for the identity of the Aboriginal peoples in John William Lindt’s photographs held in the Grafton Regional Gallery (NSW). It is an important example of a community-led approach on possible ways forward to reconnect these photographs to their descents. Along with the two authors Kate Gahan and Ken Orchard, the group of Elders part of the ‘Lindt Research Group’ has been the crucial force in this search. The Group began meeting in early 2005, and included the Gumbaynggirr, Bundjalung and Yaegl Elders Robyne Bancroft, Irene Daley, Deborah Taylor, Pam Fysh, Elizabeth Smith, Matthew Smith, Jude McBean and Sharon Sullivan. The research process has resulted in identifying 4 individuals from the Lindt images, including 5 children: Mary Ann Cowan, Harry Neville, Charlie and Nancy Whitton, and Arthur Devlin (who was identified in another Australian archive). All the photographic portraits of Aboriginal peoples taken by Lindt from the Museum’s collections, and displayed in this exhibition, are included in the sequence of portraits held in the Grafton Regional Gallery, except for two which are unique pieces (LM_f75 and LM_f71). The photographs taken by Lindt are now found in important international institutions, as well as in Australia and New Zealand, such as the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, the Cambridge University Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, the British Museum in London, the Musèe du Quai Branly in Paris, the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, the Museum der Kulturen in Basel, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Peabody Museum in Harvard, the Museum of Civilisations in Rome.